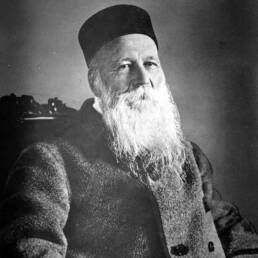

Author

Patrick Debucquois

Secretary General

Caritas Belgium (French and German speaking communities)

Every year, as Advent is approaching, the catholic Church’s readings are borrowed from “Apocalyptic” narratives, be it from the first or the second testament.

One is particularly striking:

And when you hear of wars and tumults, do not be terrified, for these things must first take place, but the end will not be at once.” Then he said to them, “Nation will rise against nation, and kingdom against kingdom. There will be great earthquakes, and in various places famines and pestilences. And there will be terrors and great signs from heaven.“

Luke: 21, 9-11

However, when it comes to reading “the signs of the times”, we need to engage in a journey.

The first step consists in practicing what Pope Francis calls a “culture of encounter”. By meeting our brothers and sisters in Christ, especially those who are suffering most, we avoid what he describes by the neologism of balconear, i.e., staying on our balconies, without engaging in the “peripheries” of our world.

Second, “reading the signs of the times” requires prayer and discernment, not least in order to “not be terrified”, but also to find the right attitudes and to act accordingly, both individually and collectively.

While doing so, we realise that a major feature of those multiple crises is of a much more permanent and global nature: let us call it an ecological breakdown.

Pope Francis refers to this when he writes about “Mother earth”, whom he also calls sister, in the same fashion as his patron saint:

“This sister now cries out to us because of the harm we have inflicted on her by our irresponsible use and abuse of the goods with which God has endowed her.”

Pope Francis, Laudato Si’ 1 – 2.

This “cry of the earth” mirrors the “cry of the poor”:

“The human environment and the natural environment deteriorate together.”

Pope Francis, Laudato Si’ 48.

The causes of this deadly evolution are manifold, and their analysis will necessarily be partial.

One of these causes goes beyond Catholic Social Teaching, as it consists of a fundamental cultural and spiritual attitude well identified and critiqued in Laudato Si’ (65 sq.): our reading and understanding of the narrative of creation, in the Book of Genesis.

This attitude has been strongly influenced by what philosophers call the “naturalist paradigm”, an occidental bias, whose main representatives are the French and German philosophers René Descartes and Immanuel Kant.

This “naturalist paradigm” gives the human reasoning precedence over nature and disconnects us from the rest of creation, in which we have become, in a certain way, like strangers. It also separates us from parts of ourselves, i.e. our senses and our emotions, some of which even seem to disappear altogether in an ever-more virtual world.

Major changes are required if we want to remedy our dramatic situation.

One of them, still largely unexplored, lies in deepening what some scholars call ecophilosophy, which is defined by Charlotte Luyckx, one of its pioneers, as “the study of phenomena which are common to philosophy and ecology”1.

A challenge for Christians in this perspective lies in revising some fundamentals of our cultural tradition while holding firmly to the position that however harmful they have proven to be for nature, human beings still enjoy a particular status, being created “in the image of God”.

Another urgent challenge is to reconsider our conception of property, which leads us back into the core of Catholic Social Teaching. Extensively dealt with in Rerum Novarum (1891), the encyclical is traditionally considered as the start of Catholic Social Teaching’s modern period. However, as brilliantly shown by Fr. Gaël Giraud S.J. in its newly published book2, Catholic Social Teaching is as old as Christianity – and another milestone can be found in Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologica, which is much more in favour of common property than more contemporary documents.

Finally, a third way to react to the trend described above consists in harnessing integral human development and its many facets, through a “formation of the heart” and the care for each creature present or yet to come. The Church invites us to take that route in the spirit of synodality, which promises to be a long journey.

1. Écophilosophie : Racines et enjeux philosophiques de la crise écologique, (Academia, 2020).

2. Construire un monde en commun – une théologie politique de l’anthropocène (Seuil, 2022).