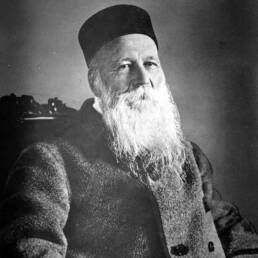

Author

Rainald Tippow

Head of Parish Caritas

Caritas Vienna

“In practice, human rights are not equal for all” states the Caritas Internationalis global campaign, following Pope Francis’ Fratelli tutti.

The pandemic, the care and concern for Mother Nature and now the disaster of the war in Ukraine is affecting and is a cause for concern for a large majority in Europe. At the same time, following the mission of the gospel thousands of parishes in our countries are not willing to accept the current state of affiars. They have Caritas groups, wit empathy towards those marginalised, because “masses of people find themselves excluded and marginalised: without work, without possibilities, without any means of escape” (Evangelii gaudium, 53).

Church’s escape in a spiritual worldliness

What is written above is only one side of the coin. The other side shows parishes and large parts of our church, focusing on what Francis calls “self-centeredness cloaked in an outward religiosity bereft of God” (EG, 97). It seems to me that across large parts of the church we see a tendency to be closed off, turned inward. This follows from decades of retreat into the private sphere, decades of self-pity after many of the faithful in our churches are frustrated because of the loss and departure of millions of people out of big national churches. Nevertheless, the end of the national churches is only the end of a special form and appearance of church. From my perspective, and that of many others, the present European manifestation of church is not church itself, much less the appearance of how it was intended by the Lord. Instead, it is only a picture of church copied in the style of the 19th and 20th centuries with roots that date back to the Constantine turning point.

This realisation is one of the biggest opportunities for the church in centuries. We have the possibility to discover the church’s vision from the beginning, in a new way, and translate it into a vision for our world as we find it at the start of the third millennium. If we take this chance, we could be liberated from the church’s state-like structures. In the work of Parish Caritas groups, in special and social projects by the church, inspired only by the spirit of solidarity and not concerned with bureaucracy, are not only pastoral task, but they are also indeed much more an act of taking the gospel seriously.

However, I feel that today in Europe we find ourselves faced with conventional, traditional and – I’ll dare to say it – “19th century parishes”. These “traditional parishes” are often marked by a few hallmarks. First, we have a strong, well maintained inner community which tends not to include new members. Second, the spiritual celebrations are difficult to understand for outsiders and finally, its members disproportionally originate from conservative sections of society. This can create a hostile environment which excludes not only the young, but many others too. It turns out that those served by Caritas, those who are called by Pope Francis the “excluded and marginalised” are outsiders and underdogs in our own parishes. They are not seen as serious partners and full members of church communities, because they behave in another way, are poor, or can be recognised as outsiders.

On the way to a strong and healthy church

At this point of history, following the pandemic and the many crises which have shaken our systems to their core, I see a great opportunity in Pope Francis’ view of the church. This seems to me to be the church of the future: “I prefer a Church which is bruised, hurting and dirty because it has been out on the streets, rather than a Church which is unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its own security.” (EG, 49)

Looking into the faces of the most vulnerable prevents the church, in all its spheres, from revolving around itself. The synodal way which we have been following this year and which continues into 2023 is an opportunity to truly look and listen to the marginalised of society. The most interesting part of a parish facing the realities of those on the peripheries is that this act prevents our parishes from a fear of the unknown and “the other” we can see so often. A church inspired by the poor and learning to read the gospel from, the poor, as Pope Francis reminds us repeatedly, is a church that sets its priorities right.

A church overlooking the poor is no church indeed.